As the marketing season falls upon us, I find myself once more attempting to articulate the mission of classical education to the general public. It is one of the most exhilarating, yet daunting, aspects of my position. On the one hand, it is an opportunity to share my enthusiasm for classical education, and my conviction that it represents a real source of hope for our troubled times. On the other hand, the difficulties involved in articulating the sources of that enthusiasm and hope are considerable. The times I have spoken with parents about classical education in the past, I have always felt dissatisfied with my remarks. No words at my disposal seem to do its merits justice.

Of course, a full account of the philosophy and practice involved in classical education would require a whole treatise to expound. So condensing that pedagogy into a talk of fifteen to twenty minutes is a great challenge. I try to focus on those features of the classical approach that differentiate it from the approach employed in most non-classical schools these days. Yet even here, there is a challenge, since much of the language that would be appropriate for describing the classical approach has been co-opted and, to a certain measure, debased by the educational establishment already. Educational bureaucrats will speak quite regularly, for instance, about teaching “the whole child,” so that when I want to emphasize the holistic nature of the classical approach, I have to carefully explain how that approach genuinely does form the whole child, and how the methods employed outside the classical school come short in this regard. It takes more than a handful of taglines to convey such things.

In order to meet the challenges of articulating the classical mission I go back routinely to the books on my shelf and flip through their pages to draw upon the insights into the tradition of humanistic learning I find there. I have gathered together some of the passages I have found recently which, in one way or another, seem to speak to the fundamental ethos of classical education. I thought it would be an enlightening exercise for others to add to this list by including passages they rely on to articulate, to themselves and to others, the core of the classical ethos. So I invite everyone to go into the comments section below, and share a favorite passage for thinking about classical education. Hopefully, by the end, we will have enough material here to help all of us in the coming year as we attempt to explain the promise of our schools to a public hungry for that promise.

Phoenix describing his role as tutor to Achilles in Book Nine of the Iliad

I was set by him (ie, Peleus, Achilles’s father) to instruct thee as my son,

That thou mightst speak when speech was fit, and do when deeds were done,

Not sit as dumb for want of words, idle for skill to move.

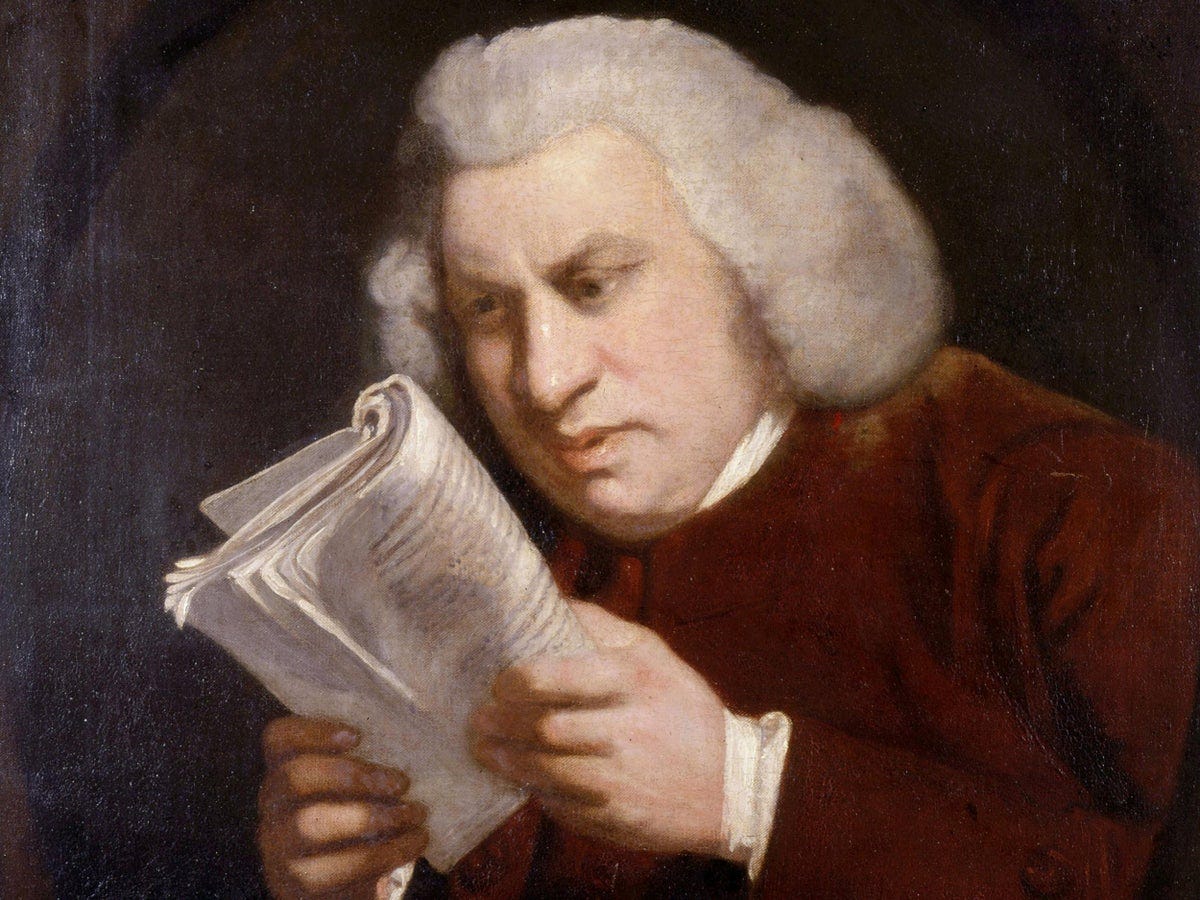

Boswell’s description of Samuel Johnson, at the conclusion of his Life of Johnson:

His superiority over other learned men consisted chiefly in what may be called the art of thinking, the art of using his mind; a certain continual power of seizing the useful substance of all that he knew, and exhibiting it in a clear and forcible manner, so that knowledge, which we often see to be no better than lumber in men of dull understanding was, in him, true, evident, and actual wisdom.

Entry in Basho’s travelogue, The Narrow Road to the Interior

We spent several days in Sukagawa with the poet Tokyu, who asked about the Shirakawa Barrier. “With mind and body sorely tested,” I answered, “busy with other poets’ lines, engaged in splendid scenery, it’s hardly surprising I didn’t write much:

Culture’s beginnings:

From the heart of the country

Rice-planting songs

From Francis Bacon’s “On Studies”

Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man.

Matthew Arnold’s definition of culture from Culture and Anarchy

Culture is then properly described not as having its origin in curiosity, but as having its origin in the love of perfection; it is a study of perfection. It moves by the force, not merely or primarily of the scientific passion for pure knowledge, but also of the moral and social passion for doing good.

From Milton’s Il Penseroso

Join with thee calm Peace, and Quiet,

Spare Fast, that oft with gods doth diet,

And hears the Muses in a ring,

Aye round about Jove's altar sing.

And add to these retired Leisure,

That in trim gardens takes his pleasure;

But first, and chiefest, with thee bring

Him that yon soars on golden wing,

Guiding the fiery-wheeled throne,

The cherub Contemplation

Boccaccio’s account of Dante’s early schooling in the Life of Dante

He gave up his entire boyhood, in his own city, to the continued study of the liberal arts, in which he became admirably expert. And as his mind and intelligence increased with years, he did not devote himself to lucrative studies as most people now do, but, with a praiseworthy desire for eternal fame, and, despising transitory riches, he gave himself up completely to his wish to gain full knowledge of the fictions of the poets and of the critical analysis of them.

Book Seven of the Analects

The Master said, “I am not one who knew about things at birth; I am one who through my admiration of antiquity is keen to discover things.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “The American Scholar”

Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state these functions are pracelled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his. The fable implies that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the other laborers. But unfortunately, this original unit, this fountain of power, has been so distributed to multitudes, has been so minutely subdivided and peddled out, that it is spilled into drops, and cannot be gathered. The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk and strut about so many walking monsters – a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.

From Letter Nine of Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man

To the young friend of truth and beauty who would inquire of me how, despite all the opposition of his century, he is to satisfy the noble impulses of his heart, I would make answer: impart to the world you would influence a direction toward the good, and the quiet rhythm of time will bring it to fulfillment.

There are several good quotes here: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/545754.Climbing_Parnassus

These are from the book: Climbing Parnassus by Tracy Lee Simmons