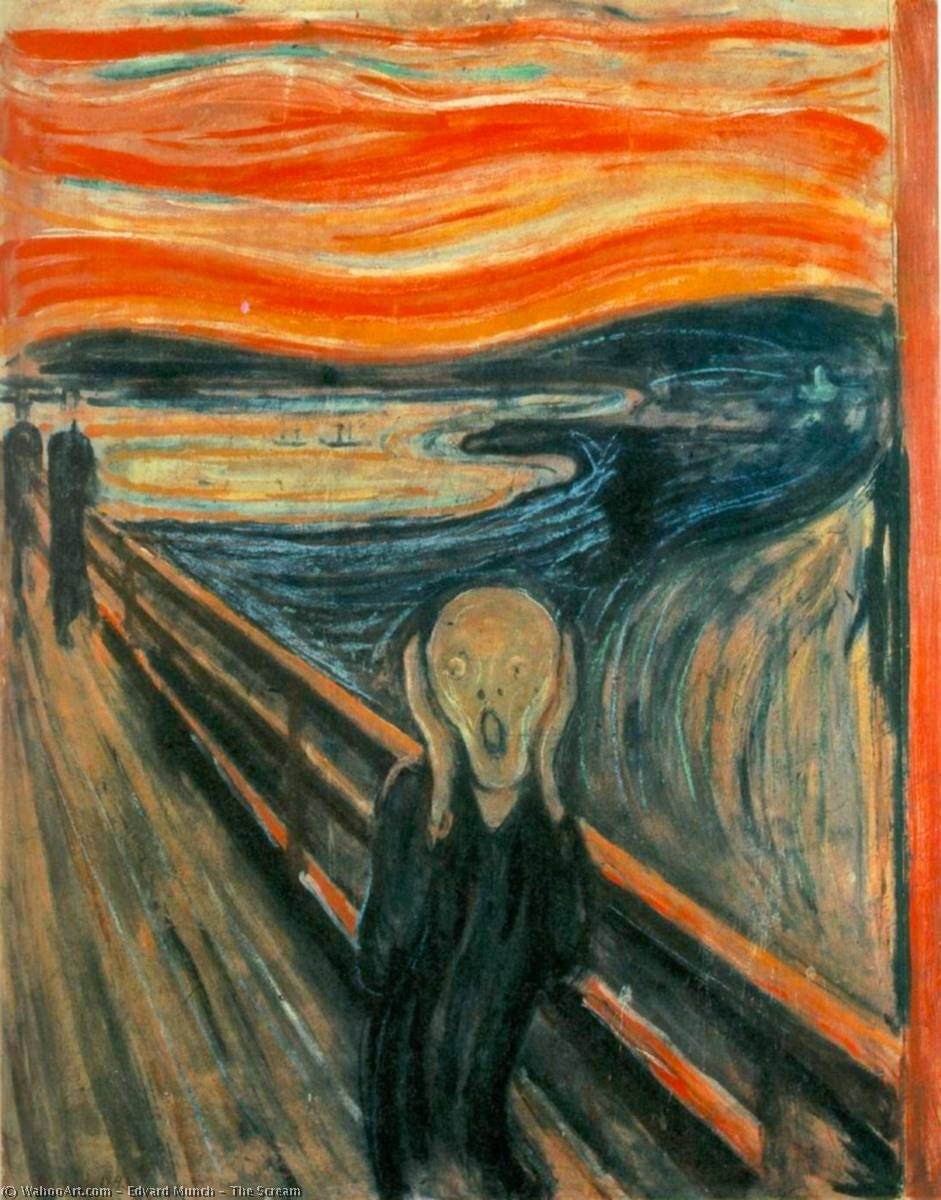

There is no more hackneyed symbol of modernity’s spiritual angst than Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” With various modifications, the painting is typically taken to represent the sense of unsettlement and dread that seems to accompany life in the modern world. In one such interpretation, the scream expresses the revulsion that arises when the mythology of the traditional conception of man as the “rational animal” is stripped away and the brutal facticity of man’s beastly nature confronts us for the first time. The scream cries out from the heart of man when he first encounters the barrenness therein.

In different ways, the nullity lying at man’s core, and the corollary tenuousness of all that we formerly regarded as fundamental to his nature – the drives towards understanding, towards ethical conduct and aesthetic distinction – is one of the great themes of our era. It emerges as early as Swift, whose depiction of the Yahoos is the depiction of man’s true nature laid bare; the scatological foulness of the creatures dropping their filth onto the head of Gulliver is meant to reveal to us the character of the animal lurking underneath the superficial trappings of civilized life. So too, the enormity of the Brobdignagians exposes to Gulliver – and to us - the nauseating actuality of the human person once all veneers are shorn away.

This basic paradigm of human nature – civility as façade, brutality as essence – becomes increasingly prevalent as time goes on. It is implicit, for instance, in the entire schemata of Darwin, whose chief point of doctrine was that there can be no fundamental difference between man and the non-human animals. Thus the spectacle in our own times of “evolutionary psychologists” asserting that everything apparently unique to man’s rational nature is really the manifestation of some underlying biological substrate – that moral behavior, for instance, is really just an epiphenomenon of the genes drive towards self-perpetuation. This paradigm pervades the vision of Freud, whose psychoanalytic theory encouraged his adherents to pierce beneath the surfaces of apparent conscious intentions to discover the sources of behavior in the dark, roiling repositories of the subconscious. In literature, this basic conception of the human person is represented most famously by Marlowe’s fateful journey down the Congo in Heart of Darkness, where the discovery of Kurtz’s horrific primal chieftaincy obliterates any possible conviction in the capacity of man to be civilized. Man is a savage everywhere, only awaiting the right circumstances to cast off the disguise of rationality and reveal the ravenous animal lurking underneath.

One inevitable, if rarely acknowledged, corollary of this picture of man is a radical devaluing of the process of education, at least as that process was once understood. If the ancient injunction laid before the student was to “know thyself,” then it is clear that this injunction becomes something much more problematic when the endeavor to know oneself reveals nothing more than the sordidness and blind willfulness lurking within. How much of the disorder and futility of contemporary education results from this basic incoherence at the heart of the whole project? How much of the utilitarian inhumanity of the modern classroom stems from teachers losing faith in the task of leading students deeper into their own humanity? The demerits of progressive education are a consequence not merely of a sterile pedagogy, but of the impoverished anthropology from which that pedagogy arises.

The paradox of our situation is that an experience of authentic acculturation in youth can actually serve as a preventative against the falsities of this modernist anthropology. To present students with the grace of a Praxiteles or the courage of the Hospitallers’ legendary defense of Malta is to open them to the possibility of a deeply sympathetic response to these things. These stirrings are themselves the evidence that something else lies there at the fundaments of their nature, something that tends towards beauty and goodness, and aches with a desire to live in the light of these great principles. On the grounds of this venerable – one might say, classical - anthropology, education may be conceived of as a series of experiences through which the divine image stamped upon our nature can steadily resolve itself within the whirl of a child’s emerging self-awareness. It is as a testament to the possibility of such an education, and as a compelling exploration of its philosophical underpinnings, that classical educators can embrace James Taylor’s Poetic Knowledge.

For Taylor, the possibility for such a form of education rests upon our capacity for a certain kind of spontaneous, basic, “prelogical” encounter with the world, an encounter mediated through our senses and emotions, and not through any rationally or critically developed concepts. This mode of experience “indicates an encounter with reality that is nonanalytical, something that is perceived as beautiful, awful, spontaneous, mysterious. …the mind, through the senses and emotions, sees in delight, or even in terror, the significance of what is really there.” What such experiences reveal to us is hardly a realm of disorder; to the contrary, even in such reflexive encounters with being, the true lineaments of both the world’s metaphysical structure and our own intellectual nature are brought to light. The mode of knowledge offered to us by this level of experience – poetic knowledge – is less definitive than that acquired through discursive reasoning, to be sure, but in another way poetic knowledge constitutes real knowledge of things, because it is the only type of knowledge that “gets us inside the thing experienced,” allows us to possess the form of the thing in our minds in the way that Aristotle, and Aquinas after him, describe what it means to know a thing.

Taylor quotes Aquinas who goes so far as to assert that “sense is cognitive because it can receive species without matter.” Sight and touch do not just show us formless masses, but particular entities, and that before we propound any conception of them. It follows that we cannot encounter the world without in some way knowing the world, that our most incipient and basic modes of experience orient us towards the truth of things. The drive towards knowing is not a labor undertaken by a discrete faculty of discursive or analytical reasoning, but is in some way the ordinary, healthy disposition of the human organism, in all of its capacities. Memory, for instance, is guided by a “natural tendency…to ‘link together various items of experience that are alike,’” and so to perceive the forms of unity pervading the multiplicity of experience. Intuition is “the spontaneous awareness of reality, that something is there, outside the mind but that the mind cannot help but know.” Appetite itself, writes Taylor (quoting Ralph McInerny), “tends towards things as they are in themselves (so that) we could thereby say that the mode of appetite is more existential than that of intellect.”

So when we pry beneath the level of conscious, deliberate, and rational action, what we discover there is not the seething cauldron of lust and anarchy that the modernist finds there, but an orientation towards being more fundamental than anything else in our nature. The world, from the first, is present to us, is knowable to us, and reveals itself to us in ways that invite our further contemplation; from the first, therefore, our experience of the world is subsumed under the regnant categories of goodness, truth, and beauty. Our most elemental desires incline us towards these transcendentals. We are rational animals all the way down to our pre-rational potencies. This fundamental disposition is rarified, specified, elaborated, and expanded as we grow and learn, but - at least in the course of our proper development - it is never wholly lost or traduced. This is why Taylor can assert that the classical tradition held, “that all the powers of the knower – senses, emotions, will, and intellect – are integrated.” To know ourselves is to know how completely, how utterly, we are made for higher things. What lies beneath the phenomenon of conscious personhood are not the monsters of the Freudian subconscious, but the seeds of a “spiritual unconscious” (a phrase Taylor borrows from Maritain), the first indominable affections of beings destined for Being.

To come to the truth of things requires, on this account, no very refined philosophical apparatus; it is a labor that waits on the propounding of no special methodology. Knowing is as much a passive as an active experience, one that depends very much on what Wordsworth termed “a heart that watches and receives.” Our primary task as knowers is “to stand and wait before an intimately knowable reality.” An educational program that does justice to the nature of the child is one that affords students ample opportunities for such standing and waiting. It is marked by a certain kind of attentive leisure, since “it is in leisure that we prepare for an active life of virtue….(and) we gain our first touch through the sensory-emotional (poetic) mode, of our final purpose, which is to experience happiness, a resting from activity, a return to where we began, to a state of repose: leisure.” Music is one of the chief practices through which this type of attentive leisure might be cultivated in students; Taylor reminds us of the extent to which early childhood education in the past meant predominantly musical education. Not surprisingly, poetry also constitutes an important form of attentive leisure through which poetic knowledge might be gained, since the practice of poetry demands our reverent hearkening to the things of the world. One of the most interesting passages in the work is where Taylor meditates on the way the monastic tradition, as established particularly by St. Augustine and St. Benedict, centers attentive leisure in its practices, which through daily liturgies of prayer, of song, of study, and of manual labor, sought to direct the soul, the entirety of the person, to God. In all of these forms of activity, modern classical educators can find models for the instruction they provide to their students.

Taylor tells a brief though incisive tale of how this classical account of the person was lost, along with its attendant pedagogical practices. This deprivation is, for Taylor, the true legacy of the Cartesian scientific revolution. In his mind, the fundamental error of Descartes was to take one mode of knowledge – the scientific-mathematical mode – and impose its method of pursuing knowledge upon the whole range of intellectual activity. The primacy of doubt enshrined in this method inevitably wore away man’s confidence in the truth-telling aspects of his aboriginal encounter with the world. As Taylor pointedly states, “to demand that each field of inquiry, that all knowledge, yield a high degree of demonstrative certainty is, finally, unreasonable.” This unreasonable conception of knowledge acquisition exerts its disastrous influence upon education in the writings of John Dewey, where a “radical application of the scientific method to education reduces the knower to a mere problem solver, doubting all, testing everything, until the problem is solved, which, for Dewey, constitutes the complete act of thought.” The aim of such an exclusive focus on “problem-solving” in the schoolhouse is to equip children to transform their society closer to some endlessly deferred progressive ideal. As the overarching aim of education, the imperative to “know thyself” is replaced by a call to “change the world.” The cultivation of poetic knowledge has no place in such a schemata; the practices of music, poetry, or simple observation of nature, through which poetic knowledge is pursued, are so many distractions from the authentic classroom task of filling students’ brains with “ideas” generated from adherence to the proper “methods.”

In the concluding chapters of his work, Taylor calls the reader’s attention to such now-forgotten writers as Andre Charlier and Thomas Shields, who, in different ways, made a case for the continued viability of a course of study oriented towards the primacy of poetic knowledge. But the figure for Taylor who best demonstrated that viability was John Senior, in his role as one of the founders of the legendary Integrated Humanities Program at Kansas University. Taylor himself was a student in the IHP, and so speaks with intimate first-hand knowledge of the tenor and practices involved in this unique course of study; these encompassed not only the reading of great books and biweekly attendance at lectures devoted to exploring those works’ significance, but also activities like star-gazing, poetry memorization, and formal dances. The purpose of all these practices combined together was not “to advance knowledge at all,” as Senior candidly asserted, but to invite students to reflect on “what must be done if each man’s life is to be lived with intelligence and refinement.” Yet one senses that the value of the IHP lay for Taylor not so much in the programmatic model it provided to educators, but in the way its enormous popularity testified to the hunger for poetic knowledge that perdures in the hearts of young people even in our own deracinated and materialistic age.

It is finally in terms of that satisfactoriness, or fittingness, that classical educators find the justification for their chosen approach to the task of teaching children. Others may boast that their curricula best prepare young people to compete in a global marketplace or to “become the change they want to see in the world.” The classical educator only claims to offer his students the right kind of encounter with being for the kind of beings they are. He only says that his program of study brings children into regular contact with truth, goodness, and beauty because children desire, above all things, truth, goodness, and beauty. The recovery of this venerable anthropology – the same anthropology that Taylor so brilliantly elucidates – is both the precondition for the work of classical educators, and the great treasure to be hoped for from their efforts. From the spread of classical schools, we might look forward to the day when young people are no longer taught to recoil from an exploration of their own natures, but through that exploration come to discover the longing for higher things implanted in the very depths of their souls.